I’d like to share with you what I learned from teaching a middle school class called ‘The Story From Day One,” which integrated mindfulness, visualization and inquiry exercises with the language arts curriculum.

We often teach myths as merely literature, divorced from the cultural, spiritual, and historical context. But we pay a price for this approach. It limits the depth of meaning students can derive from their study.

Combine this with the narrow focus on the now that social media can foster, and students easily feel isolated on an island of self, cut off not only from their contemporaries, but from a sense of the continuity of life. They have little grasp of how their lives today emerge from yesterday.

Kieran Egan, educator and author, advises in his wonderful book Imagination In Teaching And Learning: The Middle School Years, to design lessons with a narrative structure, understanding not only the skills and knowledge we want to develop but the transcendent qualities in the subject studied.

To excite students, especially middle school students who are still close to, if not seeped in, this age of magic, and who have a natural yearning for adventure and awe: Use stories of facing the extremes of reality and limits of experience, of heroes braving dangers and encountering wonders, to connect to and utilize students’ romantic imagination and emotional awareness to better understand course material.

A good way to begin is with Gilgamesh, the protagonist in the first written epic story, recorded sometime around 2100 BCE. Gilgamesh is the first literary hero, actually the first greatly flawed superhero. The story also introduces a precursor to the biblical Noah and the flood, as well as central themes that have filled literature ever since.

First There Was Breath, Then There Were Words, Then There Were Stories

The first step in teaching mythology, literature, and language is to create the space in the classroom so language comes fully alive to students. A space where they feel as well as examine what they say and read.

An old Eskimo poem states:

“In the earlier time,…a person could become an animal if he wanted to and an animal could become a human being. …All spoke the same language. That was the time when words were like magic.” The Rag and Bone Shop of the Heart: A Poetry Anthology by Robert Bly

It is difficult to imagine that words were once magic and did not only speak of ideas or convey bits of information. They were acts of creation. You said ‘sun’ and a sun appeared. You said ‘happy’ and it was so. You said ‘devil’ and you ran.

One way to make language come alive is to explore the roots, the history and stories tied to a word. In this way students get to feel how the words they use now were developed over thousands of years by millions (billions?) of people.

How many words can you name that are derived from a myth?

There are common ones like months of the year, January (Janus), or days of the week (Saturn’s-day), music, enthusiasm, ecstasy, but also logic and myth itself.

Myth has different meanings, and at least two of them seem in opposition. We commonly use myth to designate a narrative or traditional story, often sacred or about sacred beings. It can also mean fictional, untrue, as in “it is only myth” or “it is only a story,” as opposed to something factual, truthful, or logical.

Myth goes back to the Greek muthos meaning speech. Even further back to myein, meaning to close the lips or eyes. It is related to the root of mystery, which is mystes, or an initiate of the Greek mysteries. The mysteries were ritual symbolic enactments of myths, meant to transform the initiate and teach an important truth. A myth is thus speech that reveals an intuitive, unspoken or emotional truth.

Logic comes from logos, which in Greek means word or reason. Yet, in both Judaism and Christianity, logoswas used to refer to the word of God. Both myth and logic hark back to divine stories, except in one case the truth is usually unspoken or intuitive, in the other, one spelled out in rational speech.

Integrating Mindfulness with Academic Content

Start lessons with a mindfulness exercise so students can calm and clear their minds, better understand how their inner lives affect their outer ones, and notice how they respond to words, stories, and other people.

After mindfulness practice, ask questions that challenge assumptions and reveal what was hidden, so each lesson becomes the solving of a mystery. For example, before teaching the Eskimo poem or a class on language or vocabulary, ask:

Was there ever a time that you felt words were magical? Describe it. How can words (mere sounds or collections of marks on a page or device) mean anything?

Teaching The Role Of Mythology In Culture

In his book The Sacred and the Profane, anthropologist Mircea Eliade tells the story of the Achilpa Tribe of Australia. The Achilpa are a nomadic people who always carry with them a huge pole as they wander. When they stop and create new homes, they first plant the pole firmly in the earth.

Since they have no cars or other vehicles to help them, they carry very little from place to place.

So why carry the pole?

They also carry a story in which the pole is the center of their world, a pathway by which their god climbed from the earth to the heavens. If it ever fell, they believe their tribe would fall. They would be cut off from heaven.

After reading the account, I ask students: What do you think would actually happen if the pole ever fell?

The students had a variety of answers, but most thought there would be tears and fear, but nothing much would happen. They thought of the pole myth as only a story. Maybe the Achilpa would fashion a new pole, forget their old story and change their beliefs. It is difficult for any of us to step out of our own assumptions and experiences to grasp the role beliefs play in our lives.

What actually happened when the Achilpa pole fell? As Eliade explains, once the pole was broken it was “the end of the world.”

“…[T]he entire clan wandered about aimlessly for a time, and finally lay down on the ground together and waited for death to overtake them.” Which it did. (Eliade, 33)

The Achilpa belief in this sacred pole illustrates the role myth plays in culture. We often teach myths as if they were merely literature. But what is a myth? Do we, today, have our own poles that we carry around with us?

As Eliade and others show us, myths are not “merely” literature. Karen Armstrong, religious scholar and author, says myths relate us to the unknown. They are not a story told for its own sake, and many “are incomprehensible in a profane setting.” Cultural historian and author, William Erwin Thompson said myths are not just read but enacted. Joseph Campbell said they are stories that you live.

Suggested Myths to Teach in Your Class

In my Story From Day One course, we read several myths from around the world, of creation, of tricksters and of heroes, including:

The Haida (Native American) “The Raven Steals The Light,” West African tales of Anansi the spider, or the epic of Sunjata, The Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, From Europe The Odyssey and Beowulf, The modern Maori story Whale Rider.

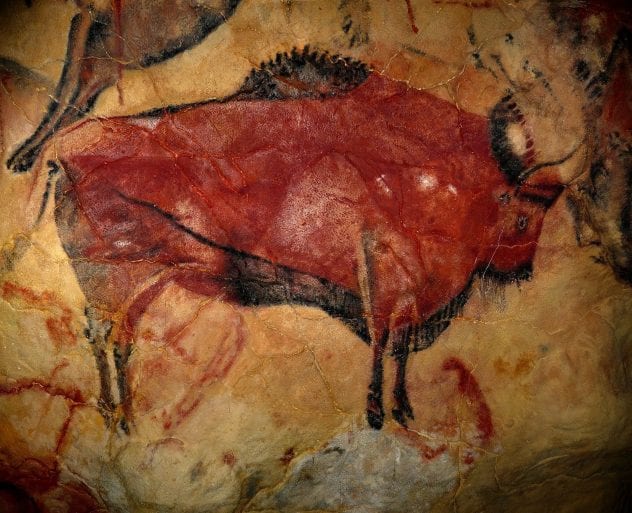

A Visualization/Imagination Exercise

According to William Irwin Thompson, in his book The Time Falling Bodies Take To Light: Mythology, Sexuality, and the Origins of Culture, imagery we use today can be traced back to the Paleolithic art caves. For example, images of bulls, horses, snakes and other animals, horns of plenty, Venus figurines, and part human-part animal shaman figures can all be found in the caves. The snake becomes the Greek Hermes. The bull, which people still fight in bull rings in some countries today, becomes Zeus, born in a cave in Crete. The Venus figurines become goddesses like Gaia and Aphrodite. The sphinx, and modern heroes like Spiderman can be traced back to the shaman of the Paleolithic caves, and to myths of Sumeria, Africa, Asia and elsewhere.

To reveal how close we humans are even today to animals and the word-magic of the Eskimo poem, I use the following exercise. (I sometimes use visualizations in lieu of mindfulness exercises) to begin the class period, focus students, and introduce material.

Ask students to close their eyes and take three relaxing breaths. Then ask: Can you feel how your shoulders expand as you breathe in—and relax, settle down, as you breathe out? Just feel that expansion as you inhale, and letting go as you exhale.

Then ask/say: Is there a particular flower that you like? Picture it in your mind. Imagine its color. Its shape. Its texture. Then notice the texture of the stem that supports it. Is it smooth or rough? Is there a scent to the flower? Is there a particular flower that you like? Picture it in your mind. Imagine its color. Its shape. Its texture. Then notice the texture of the stem that supports it. Is it smooth or rough? Is there a scent to the flower?

Then pause and continue: Is there a type of animal that you particularly like or feel close to? Imagine that from behind the flower comes this animal. Notice its color. The texture of its coat or hair. How does it move? Does it show itself all at once or gradually? Does it recognize or greet you in any way? Does it always keep part of itself hidden or does it step out into the open? What are its characteristics What is it like to sit there with this animal?

Now say goodbye to the animal in a way you feel comfortable, and watch it leave. Watch it go back behind the flower, knowing you can meet it again when you want.

Notice the flower once again. And then notice your breath. Notice the air as it passes in and out.

With the next inhalation, open your eyes and return to the room. As you exhale, notice the group around you.

Then process the experience. Have students write what they saw and possibly share with the class what they feel comfortable sharing.

Conclusion

Students are fascinated by myths because they awaken the imagination and sense of the mysterious. They illustrate how words are not only about expression or even communication but are building blocks of thought, relationship, and creation.

Myths reveal the art of world creation. We need to teach students in ways that help them better understand these worlds, their own connection to the past, and possibilities for a future. That help them better understand the depths of their own mind and what it means to be human.

Such an education turns the classroom into a portal through which wonder can enter their lives, and ours.

Also by Ira Rabois on imaginED: Education As Adventure and The Place Of Wildness And Wonder In Critical Thinking