Michelle McKay is a PhD student at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (University of Toronto) in Curriculum and Pedagogy and teaches full-day Kindergarten in Ontario.

My exploration of infusing Indigenous perspectives in outdoor education and inquiry in Kindergarten was something that emerged from contemplating how to engage in meaningful acts of reconciliation in the early years. Engaging with the Walking Curriculum and the process of deepening students’ understanding and connection to the natural world, while developing their sense of place, became a central focus of our work towards meaningful learning that is deeply connected to reconciliation.

I first learned about the Walking Curriculum when Gillian Judson spoke at our annual board conference. I was intrigued at how this type of curriculum could be used as a way of transforming pedagogy in regards to outdoor programming, specifically related to the early years. As this school year began, I revisited the Walking Curriculum text and began to consider how it could be integrated into our programming. In Ontario, we have full-day Kindergarten in which four and five-year-old children attend school for the entire day with an Ontario Certified Teacher and Designated Early Childhood Educator in the classroom. We spend time daily engaged in outdoor play and our school is located in a densely populated area with very little natural or green space for students to explore and play in. At the beginning of the year, this outdoor time was largely unstructured with a variety of materials to support various types of play. Reflecting on this component of our program I knew I envisioned deeper learning opportunities for this time, but was unsure where to begin reconsidering our pedagogy.

We decided that an important inroad to this equity work towards meaningful acts of reconciliation was to focus on the Land Acknowledgment that is read daily in our school to recognize the traditional territories our places of learning are situated on. After hearing Anishinaabe knowledge keeper Kim Wheatley speak at an event about the importance of students connecting with the land and how to make the land acknowledgment meaningful for students, I knew that the Walking Curriculum was a natural starting point. She encouraged educators to take students outside and spend time learning with the land as the first teacher. As she was speaking to us I was beginning to see natural connections between developing students’ sense of place and connection to the land with the Indigenous education and equity work we were engaging with. Knowing how little natural space we had around our school, we saw the walking curriculum as one way of connecting with the environment by utilizing students’ imaginations and grounding the walks with various cognitive tools.

At the time we began implementing the Walking Curriculum we were hoping to transform our practice and develop a sense of connection with the land, resulting in students being emotionally inspired and connected to the land. Without this connection and sense of place existing we could not fathom how we could make the Land Acknowledgment meaningful to students. Without caring for the environment, how could we meaningfully respect and honour those who the land belongs to? At first, we committed to engaging in a daily walk and documenting the learning by taking pictures and sharing our journey on Twitter. We began by capturing student voice and perspective related to what the land acknowledgment means and why we were going on walks.

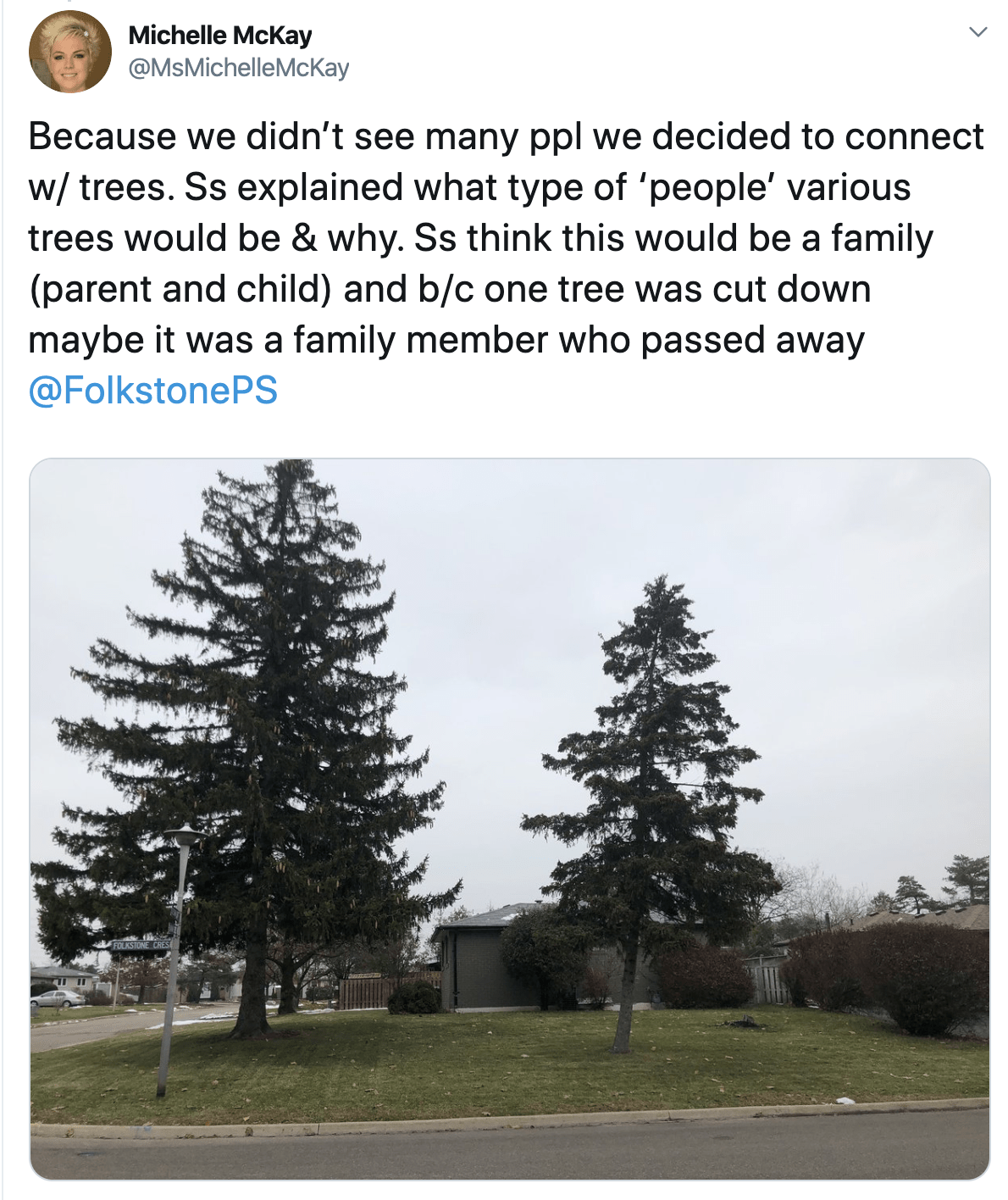

About two weeks into the process of engaging in the Walking Curriculum we began to see deep learning occurring with a sense of place developing with students that far surpassed our initial learning goals and expectations. Something that we did not initially expect was how strongly connected students would become to the various trees we encountered on our walks, specifically birch trees.

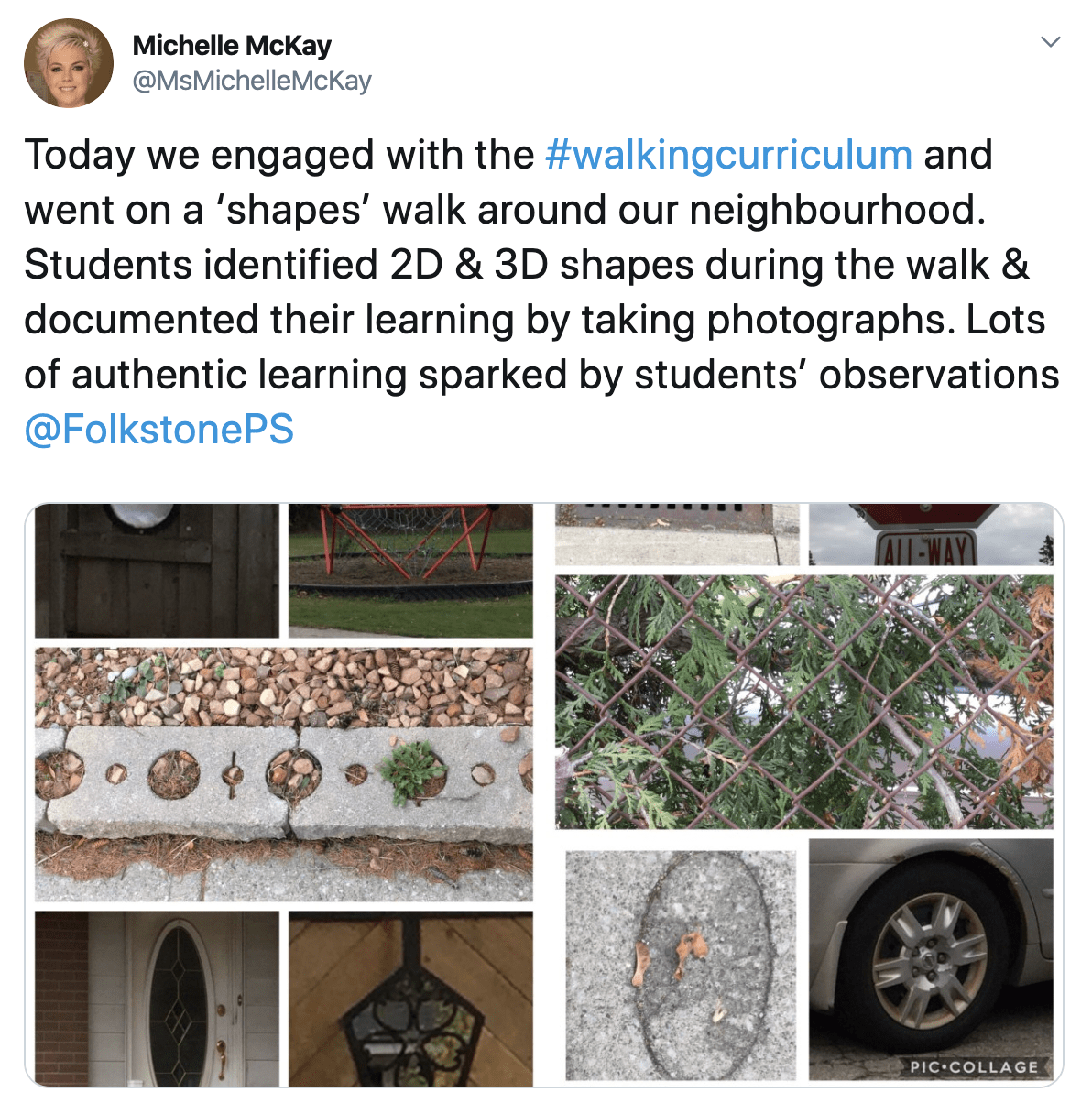

We also began to see the correlation between the rich experiential learning opportunities that were occurring and the multitude of program (curricular) expectations that were achieved.

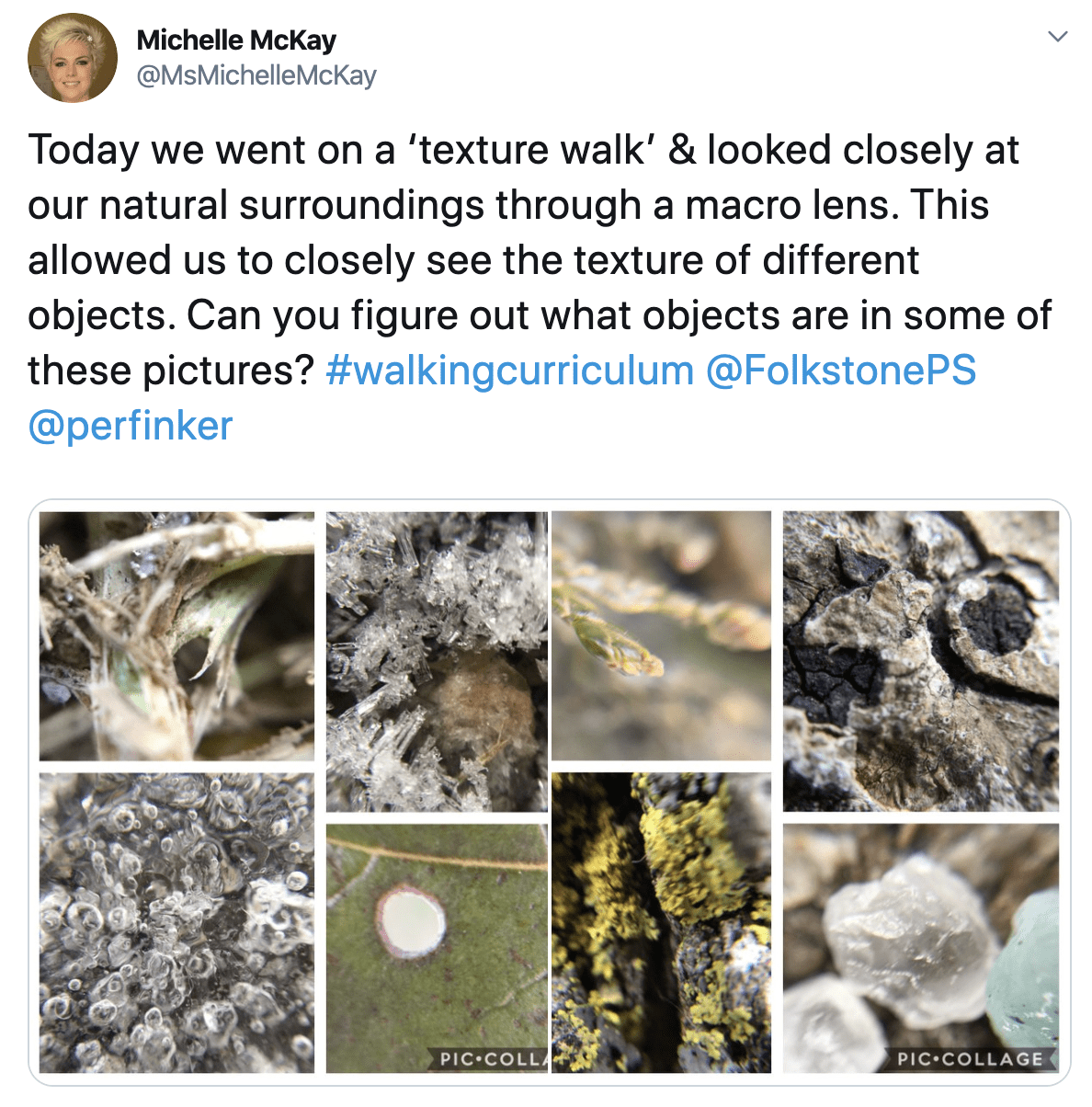

As the days progressed we began to encourage students to come up with the focus for various walks and the true meaning of the land as the first teacher became evident through various topics we ended up exploring. What we observed was that as we included more student voice and choice in the learning, the richer the learning experience became. The days that students selected the topics for walks, there were many tangents that lead to deep learning that we did not initially intend to explore.

We decided to focus the work we were doing with the Walking Curriculum and more explicitly begin to look at it with a lens of reconciliation. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada calls to Action #62 and #63 call us to engage in this meaningful work and engaging in the Walking Curriculum is our response to those calls. We developed a theory of action to guide our inquiry, which states that: ‘if we spend time engaging in walks with various curricular focuses over time to explore the natural environment then students will develop a sense of place and connection to the land resulting in environmental stewardship and meaningful acts of reconciliation’.

The Walking Curriculum is an ongoing exploration with our students with an end goal of co-creating a land acknowledgement that honours children’s connections with the land and truly respects that we are on treaty land. It has also allowed us to challenge the notion of a Euro-centric perspective of education and the lasting impacts of colonization. We are challenging the typical discourse of education and attempting to decolonize our pedagogy and practice. We end our walks consolidating our learning either at the front of the school where we discuss who the first people to live on this land were and thank them for allowing us to learn with the land. In order for students to develop the advocacy skills required to engage in meaningful reconciliation work, we want to focus on their sense of connection to the environment and sense of place/community so that they are passionate and driven to be a generation of change-makers.