By Kelsey Keller (MEd in Imaginative Education, Elementary School Educator)

By Kelsey Keller (MEd in Imaginative Education, Elementary School Educator)

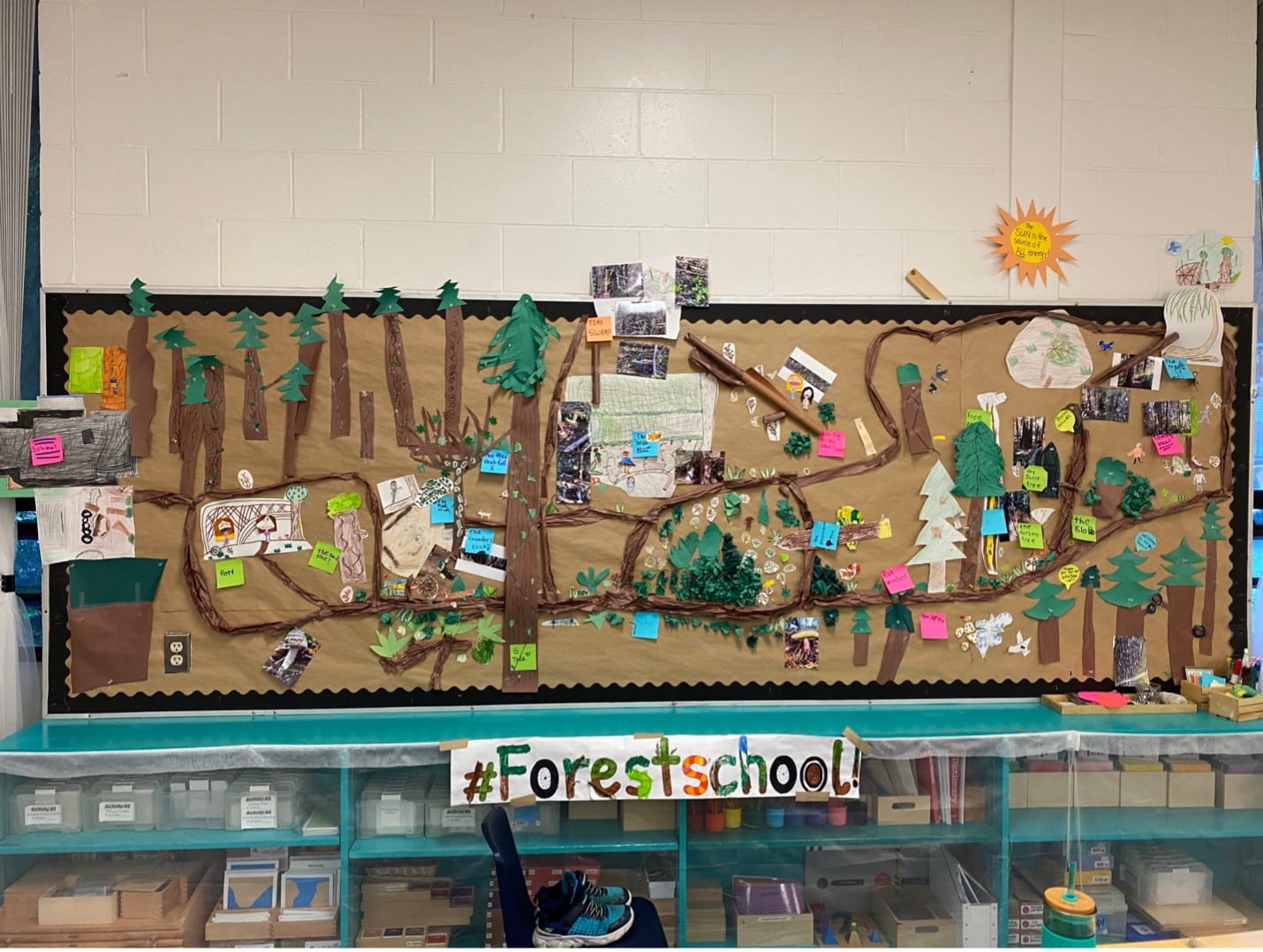

Every Thursday last year our classroom community engaged in the ritual of #Forestschool. The Forest was, and continues to be, a gracious teacher. It has offered enticing provocations; opportunities to solidify developing knowledge in experiential learning; compelling room to be restless; and the physical, mental, and chronological space to contemplate our personal connection to, relationship with, and impact on the local environment.

Restlessness

However, after months of keen engagement, I observed that the novelty of the Forest had worn off and a new restlessness emerged. #Forestschool, which had once been a source of seemingly endless enthusiasm, no longer captured their imaginations, and they begged me to extend the boundaries to make the physical space larger and to offer them novelty once again. The idea was tempting because I knew that it would very likely spark new curiosities, and the forest might once again regain their affections. While considering my options – extend the boundaries, entice them to explore deeper in the current space, or abandon #Forestschool – I once again found myself musing over the ideas of David Jardine. In particular, I re-embraced his wisdom related to restlessness. Finding reassurance in his words “…if we provide enough room for restlessness so that it might function within the space, then the energy ceases to be restless because it can trust itself fundamentally” (Jardine, 2012). I decided to lean-in to this tension and welcome the restless energy of my learners instead of struggling to remedy it.

However, after months of keen engagement, I observed that the novelty of the Forest had worn off and a new restlessness emerged. #Forestschool, which had once been a source of seemingly endless enthusiasm, no longer captured their imaginations, and they begged me to extend the boundaries to make the physical space larger and to offer them novelty once again. The idea was tempting because I knew that it would very likely spark new curiosities, and the forest might once again regain their affections. While considering my options – extend the boundaries, entice them to explore deeper in the current space, or abandon #Forestschool – I once again found myself musing over the ideas of David Jardine. In particular, I re-embraced his wisdom related to restlessness. Finding reassurance in his words “…if we provide enough room for restlessness so that it might function within the space, then the energy ceases to be restless because it can trust itself fundamentally” (Jardine, 2012). I decided to lean-in to this tension and welcome the restless energy of my learners instead of struggling to remedy it.

I decided that the boundaries of #Forestschool would remain the same. Instead of offering more physical space, I offered them time to sit in their restlessness, to lament it, to name it, to be ‘bored.’ Slowly, new novelties emerged. Some learners found previously unseen sources of joy and curiosity. Instead of going wider, they went deeper. Instead of going larger, they went smaller. Instead of going outwards, they went downwards and upwards. New appreciation grew, questions abounded, and the learners greedily devoured the new provocations offered by both the Forest and me, but it was relatively short lived. The novelty diminished almost as quickly as it had emerged.

I spent time considering how my learners had engaged in consumerism in the Forest. They consumed what they felt were its best parts, continually looking for the next ‘best’ thing, moving speedily from one novelty to the next. What I realized is that they saw themselves separate from the Forest, not a part of the Forest, and this is where my research began.

Mapping

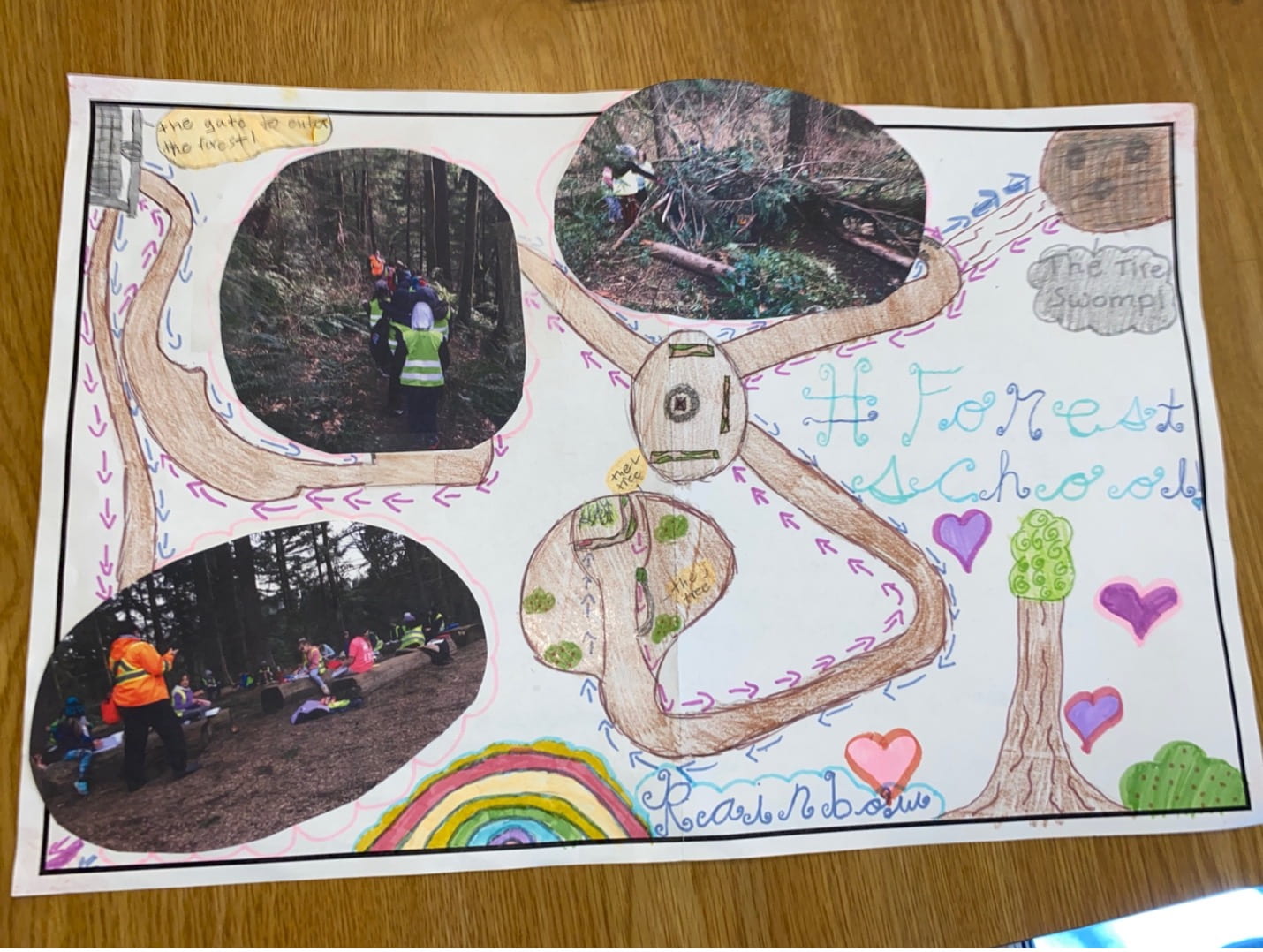

I wanted to explore how mapping the #Forestschool space might give learners an opportunity to see their own stories/connections/identities represented as integral parts of the space/place, as part of the Forest and the learners’ collective history. Instead of consuming the Forest, they would be invited to build/map it using a digital medium they were already fluent in, Minecraft. The irony of using digital technology to deepen learners’ connection to the Earth was not lost on me. I fully recognized the seeming opposition between the natural world and the digital domain, but I also recognized that this digital sphere is a world in which these learners, also ironically, feel a deep sense of belonging; is a language they speak with ease and delight; and is a medium rich in connective tissue. Instead of setting their current digital world at odds with the natural world, I saw Minecraft as a bridge that had the potential to frame #Forestschool as a relevant, meaningful, and enriching part of their modern reality.

I was curious how this process might deepen their connection to place (our local environment), how it might give purpose to their restlessness, and how it might engage their imagination through story and emotion. But we never entered the digital domain. Much to my surprise and delight, the initial lure of screen time and playing ‘my favourite game’ slipped away from their consciousness as our time in the forest and with the forest, and as part of the forest took hold of our imaginations and became part of our individual and collective stories.

Story and Emotion

We abandoned the digital realm and Minecraft. We no longer needed a gimmick to hold our interest. Maybe the ‘hashtag’ was enough of a nod to modernity. Story and emotion, two of the fundamental tenets of Imaginative Education, were the initial pillars within this research which then expanded to include restlessness, activeness, love, and place-making. I was interested in investigating how restlessness, story, emotion and the cognitive tool of mapping influenced and impacted each other, and the process of learning and place-making for my learners.

I was curious to explore how story, ‘…the unit of language that can fix the affective meaning of the events that compose it,” (emphasis added) lives within the process of mapping and how it might “bring wonder vividly to life in the students’ minds” (Egan, 2016, p. 11).

Additionally, I was interested to explore how creating a map of an intimate place may highlight the cultural elements of mapping for my learners. Would they develop an appreciation of maps as more than a collection of spaces denoted by icons and graphics, as more than a utilitarian function? I wondered how this process might elicit questions about mapping from my learners: Who made this map, and why? What stories live in these maps? What/whose stories were removed, or omitted from this map? How do my stories/maps overlap with others as pieces of a larger story? Could this whole process make maps akin to rich tapestries of culture, story, emotion, and place for my learners? I was curious to see how the learning would unfold for both myself and my learners – a curiosity that would come to feed our bodies, minds, and hearts!

References

Child and Nature Alliance (CNA, 2021). Forest and Nature School Practicitions Course. Retrieved from: https://childnature.ca/forest-school-canada/

Egan, K. & Judson, G. (2016). Imagination and the Engaged Learner: Cognitive Tools for the Classroom. Teachers College Press.

Jardine, D. (2012) Pedagogy Left in Peace: Cultivating Free Spaces in Teaching and Learning. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Hi Kesley,

Thanks for sharing your forest ad-ventures. Nature nurtures awe but can also become the norm.

You mention restlessness. So very true. I would also look into the hidden lining of boredom.

Holly