Michael is a teacher on the unceded territories of the Salish peoples, a doctoral candidate, and occasionally a poet. He’s a member of the Academic Council for CIRCE and teaches graduate-level teachers on an Imaginative Education approach to learning. He also likes long walks in the forest.

After all, while this plague enforces a temporary distance from other humans, there is no reason not to lean in close to other beings, gazing and learning—for instance—the distinguishing patterns of the bark worn by each of the local tree species where you live. No reason not to step outside and pry open your ears, listening and learning by heart the characteristic songs and calls of the various local birds; no reason not to apprentice yourself to a spider as it weaves its intricate web in front of the porchlight.

— David Abram, “In the Ground of Our Unknowing” (2020)

While Covid-19 has forced many students to learn on-line, I wanted to take up Abram’s advice and suggest a few activities that might combine “idle” and attentive free-time outdoors with some creative writing and arts-based activities. Teachers and parents might encourage children to link these directly to their LiD topics, but I am also of the mind that getting outside for some wander time with some loose educational directives, whether it is linked explicitly to the topic or whether those links come later, is time well spent. Given the schedules and realities of conventional school-life, there are relatively few opportunities for students to idly contemplate their LiD topics in a park, in the backyard, on a walk, in a sit-spot, in the relative isolation “offered” by this “event.”

The three activities are each inspired by wonderful books I have come across and I suggest, after introducing the key elements, the first step is getting outside to wander about a little or choose a “sit spot” for some open-ended observation time. You do not need the books to do the activities per se, I will include links to the publishing sites and an example from each below.

1. Shoot and Scrawl

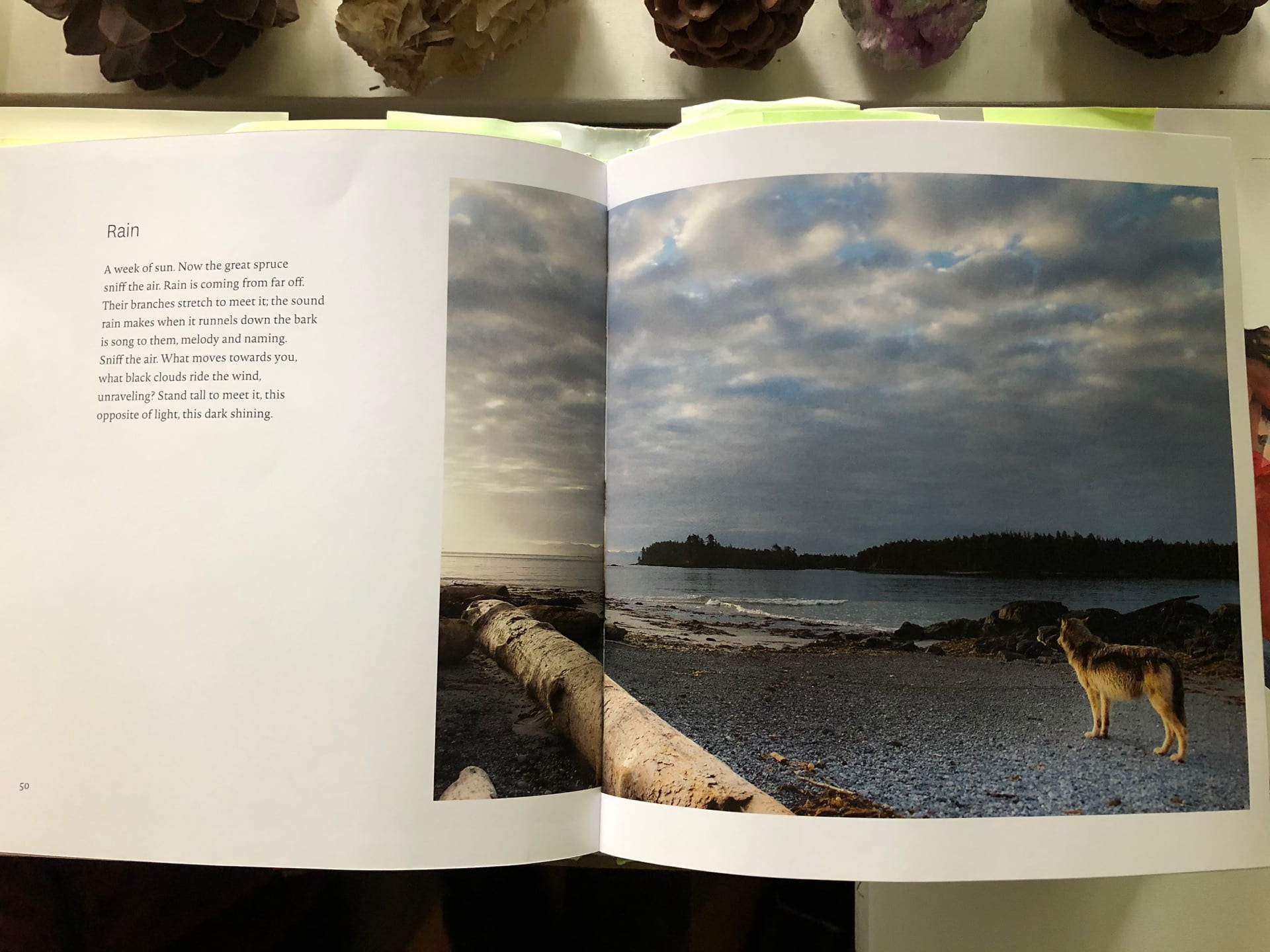

The first activity is based on a collaborative book by Victoria-based poet Lorna Crozier and photographer Ian McAllister called The Wild in You. The book combines nature photography with a complementary poem (although reflective journaling, an inspired story, or “scientific observations” could also accompany the photos).

There are several variations. Sometimes I invite students to imagine they are National Geographic photographers and their assignment is to go out and take 20 photos, come back, select the three they think are the most evocative, and have them write something inspired by those photographs. If you have siblings or a group you can get one person to take photos and the other to select their favorite shot to write about, then switch.

As extensions you might also get students to imagine they are either travel bloggers or Instagram poets and post their photos and writings on-line (there are tons of platforms for this, I have used Squarespace). Reading a few of Lorna Crozier’s wonderful poems and trying to take some of your own photographs to accompany her pieces is also a nice, writing-free way to explore both this book and your local places.

2. Artful Acrostics

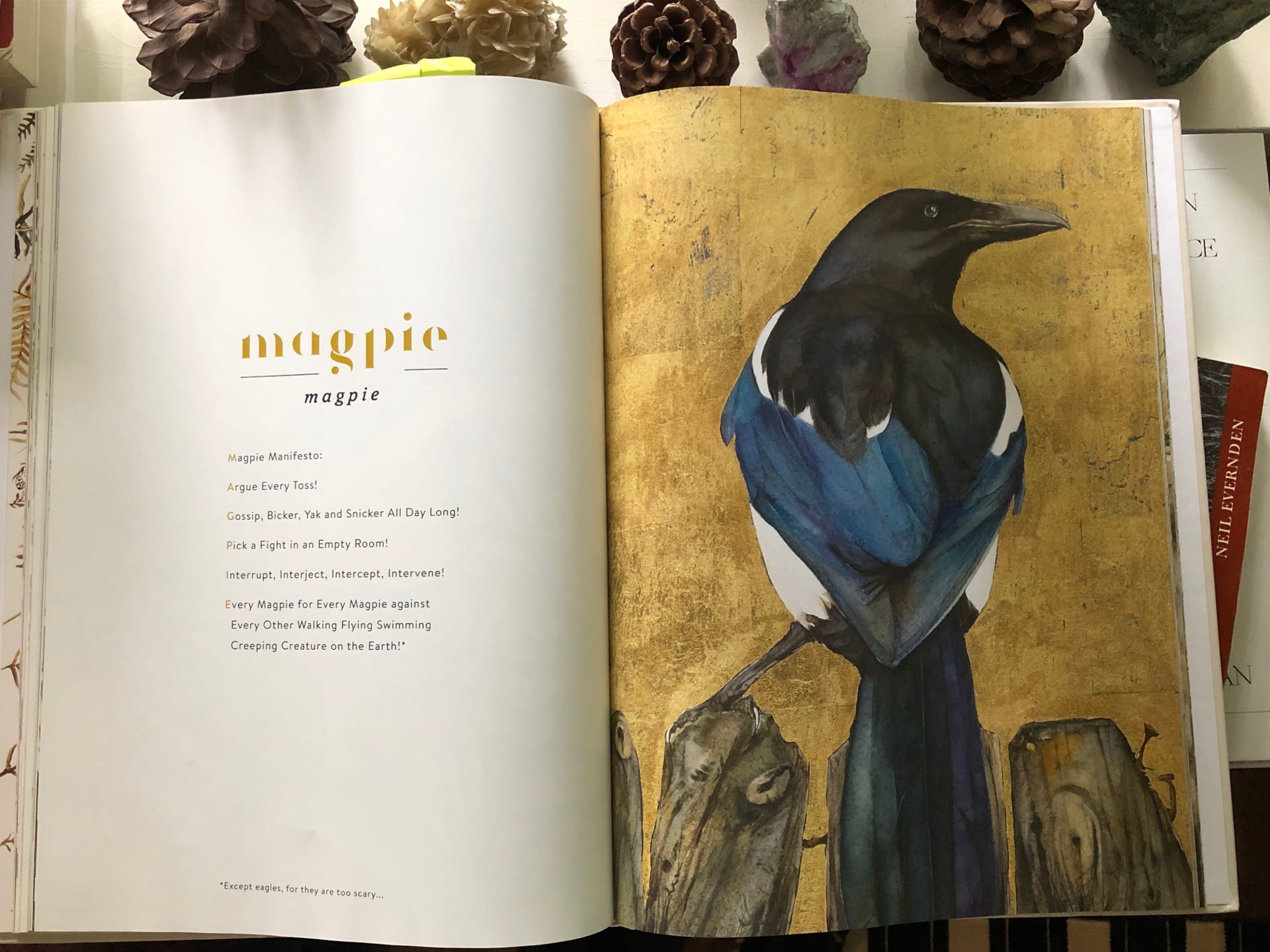

The second activity is based on a gorgeous book by Robert Macfarlane and illustrated by Jackie Morris called The Lost Words. The book was inspired by the removal of 50 nature-based words (e.g. acorn, buttercup, fern, etc.) from the Oxford Junior Dictionary to make room for words like “broadband” and “cut and paste.” Due to this book, protests of those like Margaret Atwood, and general public outcry, the decision was highly contested.

Similar to the previous activity, this one first involves getting outside and paying bright attention to those things, plants and creatures we are often too quick or busy to notice. What is that flower called anyways? This may require breaking out a field guide or the many plant/bird/animal apps available—but a common dandelion or banana slug works just as well.

The Lost Words combines sketches and paintings with acrostic poems, those infinitely entertaining ones that take the subject, let’s say sword ferns, write the first letter vertically down the page and then create a poem where each line starts with S then W then O, etc. The activity lends itself to sketching or water colours and the nice thing about acrostic poems is that they can be as simple or complex as the writer chooses.

For older students, an outdoor discussion about the role dictionaries play in shaping our perception of what matters (perhaps based on The Guardian’s article about the Oxford Dictionary) might be a great way to engage those nascent philosophic minds.

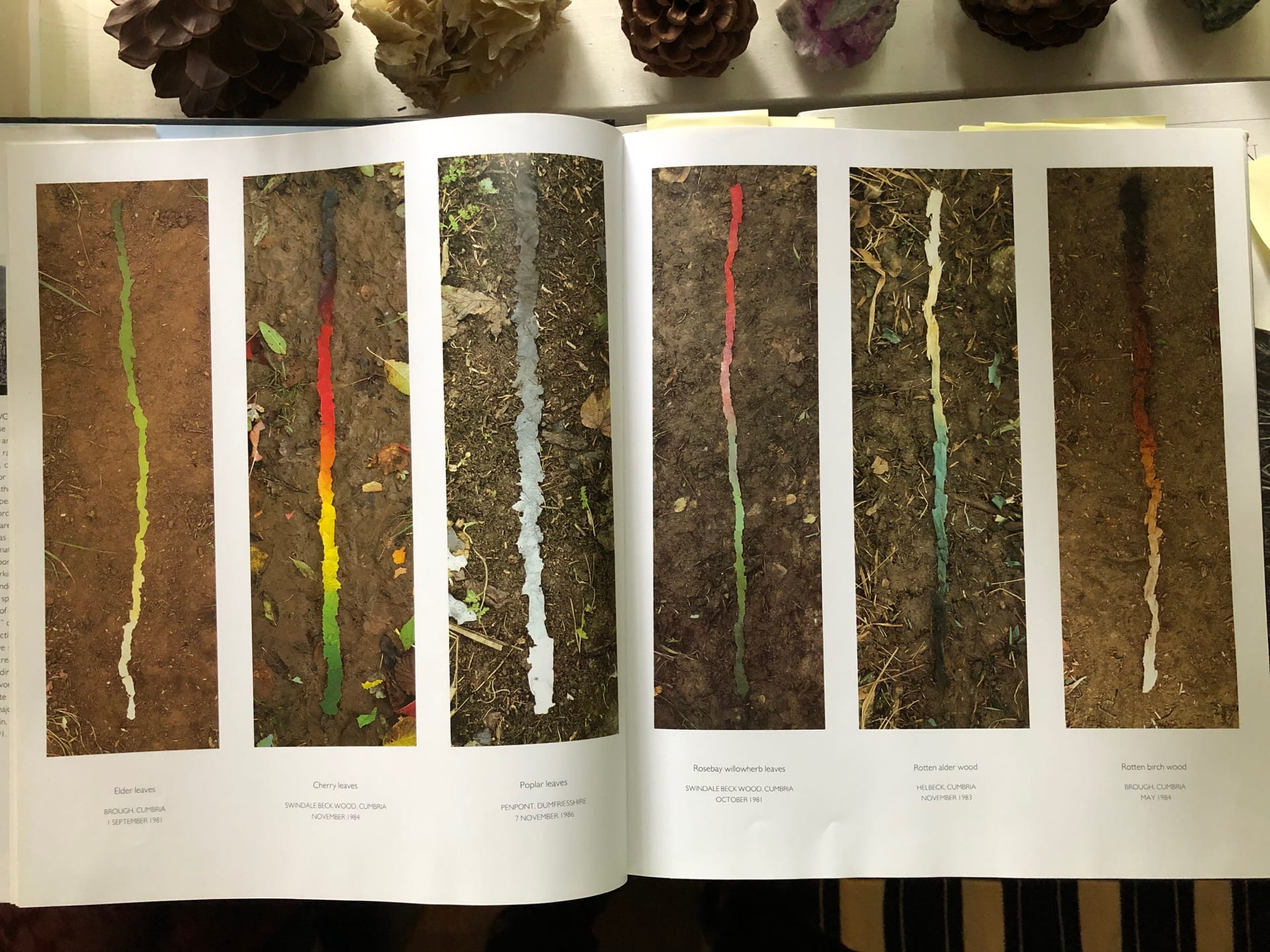

3. Nature’s Canvas

The final activity is based on the work of Andy Goldsworthy. Any of his books serve as a good example, but there are also two documentaries and plenty of images on-line (links below).

The lack of writing in this activity tends to appeal to students. For younger students I have them try to emulate one of Goldsworthy’s works, usually one of the simpler rock or leaf pieces. For older students, I have them do the same, and then debrief with some/all of the following prompts:

What is unusual about Andy Goldsworthy’s approach to art? How does this kind of interaction with nature affect you? What eventually happens to Goldsworthy’s outdoor artworks? What do you think about art that is made to fall apart? What sort of artist is Goldsworthy? Is he a sculptor, or more of a performance artist? How might the fine arts influence efforts to promote conservation?

Remember: the only rule is that you cannot “kill” things to create the piece, only fallen leaves and twigs and be respectful of stones that may be homes for other creatures.

Goldsworthy Links

- Rivers and Tides Documentary

- Leaning Into the Wind Documentary

- “Magical Land Art By Andy Goldsworthy”

Final Thoughts

It seems to me that if there is time and means—and I recognize many are struggling—and if it is feasible to get students to safe and relatively biodiverse places during all this, the most “innovative” thing we can do educationally is to engage a thoughtful combination of senses and mind. If it ties directly into a LiD topic, wonderful, if not, well part of the process of LiD is making connections. Given that the core of ALL learning, from an Imaginative Education perspective, is embodied and somatic I think it may be in our students’ best interests (not to mention our own) to take up the call and lean in close to other beings.

References

Abram, D. (2020). “In the ground of our unknowing.” Emergence, Vol. I. Retrieved May 25th 2020 from https://emergencemagazine.org/story/our-unknowing.

Crozier, L. (2015). The Wild in You. Vancouver: Greystone Books.

Flood, A. (2015). “Oxford Junior Dictionary’s replacement of ‘natural’ words with 21st century terms sparks outcry.” The Guardian. Retrieved May 25th 2020 from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/13/oxford-junior-dictionary-replacement-natural-words

Macfarlane, R. (2017). The Lost Words. London: Penguin Random House.

Interested in Reading More?

Interested in Reading More?

If you enjoyed this post, check out Michael’s other instalments in his Learning in Depth Series…

Thank you Michael for this inspiring blog on observing and responding to nature. The books you highlighted look wonderful, and I will be looking them up. Another nature/writing activity I can suggest is watching the activity at a bird feeder. My bird feeder in Lake Country is visited by Evening Grosbeak, Spotted Towhee, House Finch, Pine Siskin, Goldfinch, Black-capped Chickadee etc. I have noticed a pronounced variation of ‘personality’ within a species; behaviour which reflects timidity, boldness, gregariousness, greediness, and so forth. I wonder whether there are hierarchies within species/across species. I wonder whether there exists a universal body language which enables various species to communicate. I wonder whether the bird feeder also serves as a communication hub. With these musings and others, students could be encouraged to write a creative story, personifying personal dramas in the activities of a bird feeder.

What a timely post! Thank you, Michael. I just received The Keeper of Wild Words by Brooke Smith – a beautiful picture book inspired by the Guardian article you referred to. I can’t wait to pair it with Lost Words! I have made a real effort this year to take my students outside, to let them experience our Place, using all of their senses. Each morning, we spend the first half hour of our day outside, rain or shine, playing in the “forest” (a stand of trees at the front of our school), and each afternoon we use The Walking Curriculum by Gillian Judson, to take a focused walk on our school grounds. I am seeing in my students an awareness and an appreciation for their natural surroundings that I haven’t seen in years past. Even when they are playing they are noticing and wondering, and they are eagerly sharing their observations and wonders with others. Slowing down, and giving time and space to explore has led us down some really interesting paths that we would not have followed without these explorations. I am also pleasantly surprised by the number of cross curricular connections that have come up organically through this relatively unstructured time.