During World Creativity & Innovation Week (April 15-21, 2018) I had the pleasure of moderating a week-long conversation on imagination with the Google+ Creative Higher Education (#CreativeHE) community. My imaginative colleague Jailson Lima from Vanier College, Quebec, moderated with me. You can read the whole week of conversation on Google+ in the Creative Academic community space here. My intention is to highlight some of the ways in which my Higher Education colleagues employ walking-focused practices in their teaching. The focus on walking emerged after we posed an imaginative challenge on Day 3. (New to imaginED or the walking curriculum? Learn more here or purchase The Walking Curriculum: Evoking Wonder And Developing Sense of Place (2018).)

The Imagination Challenge: Get Outside

Here is the challenge we posed on Day 3:

Greetings imaginative colleagues! Sometimes we need to change our contexts (eg actual locations, ways of engaging, practicing or thinking) to get our imaginations going; we need to purposefully step outside of our typical practices to more easily envision new possibilities and alternative perspectives.

The goal of this challenge is to stimulate the imagination of someone else and the challenge requires you to literally (and figuratively) get outside. We want you to take a walk with wonder and curiosity guiding you. Have something in mind that you teach or you might help someone else learn. Let your wonder and curiosity guide you in noticing what your local community might teach. What lessons or knowledge does the Place afford? How is your imagination ignited?

If you are a teacher or educational developer seek the affordances for teaching/learning this topic outside. What imaginative task or activity might your students do while outside (walking or in stillness) that could enhance their imaginative engagement and meaning-making and enable their creativity to flourish?

Walking For Understanding: #story vs #story-form

I decided to focus on how I might teach the difference between the/a “story” (could be fiction/non-fiction, the content is key) and the “story-form” (more to do with the shaping of the information. Evoking emotional response/imagination is key) through a walking-focused, imaginative activity. I find this is a concept that many of my students (experienced teachers) can struggle with. Educators have deeply rooted notions of “story” and its role in their teaching. No matter how many times I seem to talk about using the story-form in teaching (or that our teaching can be viewed as story-telling and us, story tellers) and despite many examples, a significant percentage of my students don’t seem to really understand the difference. I see the misunderstanding or limited understanding in their assignments and reflections. Many miss the profound power of the story for learning and believe that teaching as story-telling means that they must tell actual stories (the who/what/why/ when/where) or create fictions for their teaching. Clearly my teaching is falling short. Maybe an experiential, emotionally and imaginatively engaging activity will deepen understanding?

My idea: Ask my students to explore the community around campus. They would be tasked to capture images (they could evoke them later with words for us; or take pictures) that would either fall into the #story or the #story-form category. We would debrief their choices and, in the process, more deeply understand the power of the story-form as a way of human thinking/teaching.

Here is what I came up with on my walk:

#story-form (Collage) How do kids learn about the seasons? About Spring? Teaching about Spring could be shaped in a story-form if we focused on colour. We can use colour as way of emphasizing the metaphorical (and literal) sense of rebirth and new life. The MAGIC of spring—the surprise? the beauty? (What heroic quality could shape the narrative?) We could frame the actual biological process of life cycle of plant and/or situation of the Earth with dramatic emotional ideas of life/death or renew/end.

(Note: #notstory-form: “Spring is one of the four conventional temperate seasons, following winter and preceding summer.” (wikidpedia) ….) A collage of the #story-form images I took on my walk:

#story-form (Video) I was also thinking about my walking on my walk…What’s the story on walking? Evoking a #story-form about walking might focus on what Dan Rubinstein (author of Born To Walk) calls “the maginificence of bipedalism”. A story-form evokes the wonder, life- and world-changing impact of humans getting up on two feet. I can’t seem to easily upload my video here but you can see it in the Google+ space #story-form (Video)

#story (Collage) Here I have images of particular things happening in my community or evoking something historic. I’ve made a collage of the images. The content is key.

Think—This is a local community arts project using ribbon. The next two words are “and wonder”

Vacant Lot—This lot is at the centre of a controversy between landowner and developers. Lawyers hired!

Street Corner—This is the site of a tragic shooting a few years ago.

A nut—One chestnut. In the middle of the school field. How did it get there? What has this chestnut experienced?

Wooden village—For days local kids have been collecting sticks and building this village in miniature near my home in a local park. It is alive with stories for these children!

Bird house—Someone built this home to feed the birds–was it sunny on the day it was hung on this fence? How did it end up crooked?

In telling these “stories” I could, of course, teach about different moral lessons or ideas of social importance. Also, my telling will be more engaging if I use cognitive tools but these are “stories”. Specific, defined.

The next time I teach about #story vs. the #story-form we will be walking.

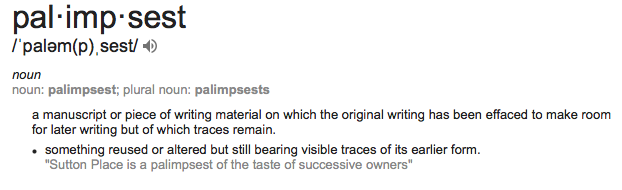

The Palimpsest Project (Jailson Lima)

Jailson shared an historical project in which walking and exploration are deeply connected to pedagogy.

“In the 1990s, I taught high-school chemistry at the Colégio Vera Cruz, a private institution in São Paulo, Brazil. During one academic year, 12th graders developed a project called Palimpsests in which they were asked to look at cities as something having diverse layers or aspects that usually remain hidden beneath the surface. In the first phase of the project, students walked around the school’s neighborhood to explore the landscape, looked at its topography, took pictures of buildings, houses, parks, etc. Later, those pictures were compared with older pictures available in the local library so that students could create awareness that cities are constantly changing.

Later, the project focused on the city of Rio de Janeiro during the 19th century, a period in which the city was the nation’s capital. Excerpts of novels, essays, official documents, and paintings of the period were used to contextualize and integrate the different disciplines—history, geography, literature, and the visual arts. The topics were complementary and created a mosaic that was analyzed through a multidisciplinary perspective. The group took a field trip to Rio de Janeiro in search of the 19th-century layers of its modern palimpsest—governmental buildings, historical houses and commercial centers, and the old port. This, of course, required a lot of walking too. After the trip, students watched movies based on literary works of that period, which gave them the opportunity to experience 19th-century novels through the lenses of 20th-century cinema. The pre-readings, field trip, and post-activities created a continuum that helped students developed a sense of seeing cities as palimpsests. Being exposed to this project as a teacher, changed my own perspective and made me aware of the richness of seeing cities as palimpsests. When visiting ancient cities like, for example, Rome, I now look at them and try to separate their layers: Imperial Rome, Medieval Rome, Renaissance Rome, Modern Rome, etc.

Now I live in Montreal and teach in a college whose building used to be a convent for nuns. Montreal does not have thousands of years of history like Rome, but a visit to the old port can teach about the ways humans choose to build their cities: the availability and proximity of water sources, the accessibility of means of transportation, etc.”

Walking around the Vanier college campus, I pass by two small 19th-century graveyards, and I wonder how many students actually notice them. Just analyzing those gravestones would be a history class in itself. The Palimpsest project starts with a walk around the neighborhood, and it can be easily adjusted to the specifics of each city. It is a great way to connect students with their surroundings and give meaning to ‘school stuff.’

Please get LEAVE A COMMENT. Do you #getoutside in Higher Education teaching? If so, how does Place influence your teaching?

Stay Tuned for Part II!

This is a wonderful way to connect students to “place”. Both articles brought me out of the classroom (metaphorically at least) and had me imagining being there. For my students, I wish upon them these opportunities to bask in their surroundings and to truly enjoy the wonder of it all.